Phishing: setting up a false website, looking more or less like the bank’s site, and getting users to enter their username and password, so that the phisher can then log on to the bank himself and empty the user’s account.

Admittedly, the preceding paragraph took some freedoms with the definition of phishing, but I’m discussing just banks now, so let’s leave it at that.

The preceding paragraph also assumed that the bank uses username/password logon, which is not always the case. Depending on how one logs on to the bank, a number of scenarios for phishing develop:

Username and password

These sites are ridiculous. You get the username and password and you can log on and transfer money to your heart’s delight. You can obtain the username and password through a lookalike site, pretending you failed to log on and collecting the passwords that way. You get the user to go to your site by sending out email with a link to your site, saying something like “your account has been suspended and you must log on again to enable you to keep using it” or some such drivel.

Banks with OTP scratch cards

Some banks issue cards with one-time-passwords (OTP). You have to log in using your username and the next code on the card. You get to see the next code by scratching off the silver layer covering it. In some cases, you need a second code to confirm transactions. In some cases, the transaction codes are not on the same card, or not in the same series, as the logon codes. That’s good, because a fake website that collects logon codes by “failing” to login twice in a row will only collect logon codes and no transaction codes.

Note that if the phishing site connects to the bank in the background, it can allow you to actually log on to the bank and perform all your transactions. Meanwhile, the phisher can modify your transactions, for instance by changing all the account numbers you send money to, to point to his own bankaccount, or that of an accomplice. You’ll never notice, until people start complaining about not getting paid. This kind of attack is a man-in-the-middle (MITM) attack.

Banks with hardware tokens, timebased

If you log on using a hardware token that changes it’s (usually) 6-digit number every minute, you don’t risk having someone get your password and use it behind your back. It’s only valid for a minute after all. (There’s a “window” of a few codes on both sides, so it could be anything between five and 10 minutes, actually, but that’s another story.)

But if you’re talking to a MITM, he’s just forwarding the logon screen from the bank to you, and your logon password from you to the bank, so the hardware token hasn’t helped you one bit. The same goes for the signing of the transaction, since it’s done the same way.

Hardware token with challenge/response

A lot of banks start to use challenge/response hardware tokens. This is probably the best method so far, but it still stinks. If you have a MITM, again he’s forwarding the bank’s pages to you and your responses back to the bank, so the hardware token makes no difference.

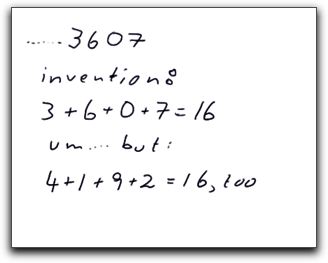

The hardware token is also used to sign the transactions. That is, a number is calculated from your transaction list, including account numbers and amounts, and that number is sent to you. You input that number into your hardware token and calculate a new number, a “signature”, that you send back to the bank.  There is no way for the MITM attacker to change your actual transactions without the challenge number changing. Sounds great, right? Except… if your challenge number changes, how would you know? It’s just an eight digit number, which reflects your transactions according to some undisclosed formula, so you have no way of knowing which transactions you’re actually signing! That’s ridiculous!

There is no way for the MITM attacker to change your actual transactions without the challenge number changing. Sounds great, right? Except… if your challenge number changes, how would you know? It’s just an eight digit number, which reflects your transactions according to some undisclosed formula, so you have no way of knowing which transactions you’re actually signing! That’s ridiculous!

One bank I’m using uses the total amount of the transactions as one part of the challenge. That is great! But… the account numbers aren’t part of it. So as long as the MITM doesn’t change the amounts, he can reroute the money wherever he desires.

Pretty Pictures

Some banks have gotten the brightest of ideas: let the user select one or several pictures he likes and present these to him before he logs on next time. A phisher wouldn’t know to show the right pictures, and the user would notice. Except it doesn’t work.

To be able to present these pictures to the user, the bank first needs at least a username. Well, what do you know, even the MITM can give that to the bank. So, the user sends his username to the MITM, who sends it to the bank, who sends the pretty pictures to the MITM, who passes them back to the user.

End result? That the user is now convinced that the MITM phishing site is authentic. The bank told him so, didn’t they?

Machine certificates

Some banks send their users certificates to store on their computers. The bank then has two strategies:

1. Some banks show the pretty pictures after reading the certificate. No certificate, no pretty pictures, and they fall back to other authentication methods.

2. Skandiabanken.se: you can’t log on without the certificate. But, of course, if you don’t have one, you can get one.

What’s my problem with these two methods? First, the fallback method is often a weak point. The other problem is with the certificate itself.

Skandiabanken relied on machine certificate plus a regular username/password logon until december last year, when they suddenly and without warning sent out OTP scratch cards to everyone and added a onetime code to the login, overnight. They refuse to talk about what went wrong, but it’s obvious that the machine certificate was not enough security. Maybe it can be stolen? Maybe a machine trojan can use it to log on? I don’t know. But I do know that Skandiabanken does not trust machine certificates anymore, so neither should you.

So what does work, then?

I have a fair idea. First, forget about logons, they’re not that important. We can secure those with hardware tokens or scratch OTP. We can’t guarantee that there’s no MITM snooping on us, but we can guarantee he’s not stealing our money if we use digital signatures on human-readable bank orders. This is how that could work:

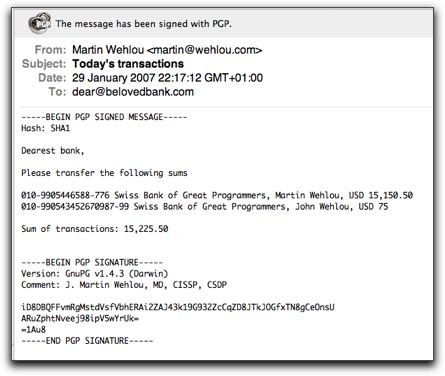

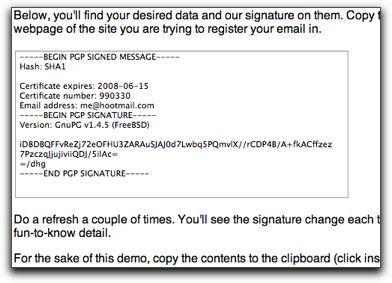

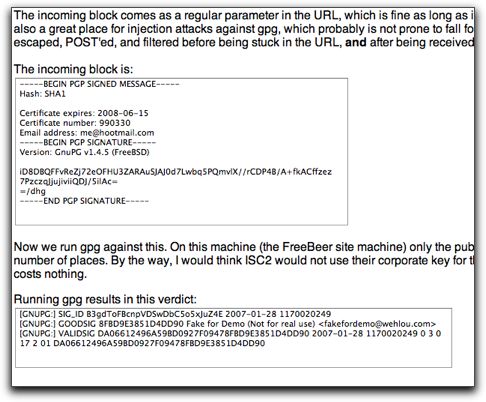

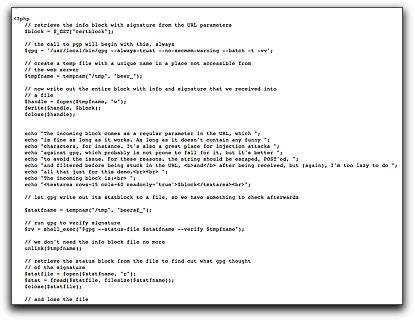

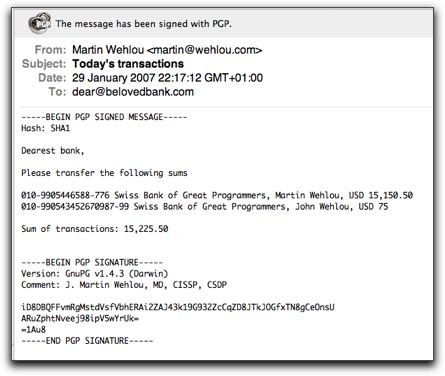

You log on to the bank site and enter all your transactions. At the end, the bank creates an email message for you by opening your mail agent (Outlook Express, Mac Mail, Eudora, Thunderbird, whatever), addressing the mail to itself, and as body of the mail it enters a completely readable list of transactions with account numbers, names, amounts, everything. The user then clicks the “Sign” button in the mail agent and adds his digital signature to the message and out it goes. A couple of minutes later, the bank retrieves the message, verifies the signature and executes the orders.

It’s that simple.

The only thing standing in the way of this is getting digital signature software installed in end-users’ machines. And getting the digital keys and certificates set up. This is not rocket science and could easily be achieved if the banks put their minds to it. And if they stopped shrugging it off as something “too difficult”. It isn’t. It’s easy.

Note that it doesn’t matter how many MITM attacks you have in this scenario. The transactions are inviolate. You may need some technology to protect the user’s keys, though, like smart cards. But not even this is very hard to do.

Nothing else that I can see has a remote chance of standing up to MITM attacks.

We’re not home quite yet, though. We have to consider that the signing operation can be compromised. As long as the software that does the signing runs on a computer that can be compromised, so can that software. It may need to be hardened, it may need to use the Trusted Platform stuff, it may have to be taken off-system. But at least we’ve reduced the problem considerably, and by doing that have a fighting chance.

Just sticking more virtual keyboards, pictures, and magic phrases into logon pages isn’t doing anyone any good. It’s nothing but security theater and instilling a false sense of security.

PS: I just noticed that the domain “belovedbank.com” that I used in my example mail is free. Go for it, guys!

security

security

The first time I went to a tech talk was about a year ago and the room was half full. I then asked a couple of the people who attended, and they all said that it was about the same number as previous years, same old crowd, hardly any new faces. I found that disappointing, because Apple with OSX had already become an interesting phenomenon then.

The first time I went to a tech talk was about a year ago and the room was half full. I then asked a couple of the people who attended, and they all said that it was about the same number as previous years, same old crowd, hardly any new faces. I found that disappointing, because Apple with OSX had already become an interesting phenomenon then.

There is no way for the MITM attacker to change your actual transactions without the challenge number changing. Sounds great, right? Except… if your challenge number changes, how would you know? It’s just an eight digit number, which reflects your transactions according to some undisclosed formula, so you have no way of knowing which transactions you’re actually signing! That’s ridiculous!

There is no way for the MITM attacker to change your actual transactions without the challenge number changing. Sounds great, right? Except… if your challenge number changes, how would you know? It’s just an eight digit number, which reflects your transactions according to some undisclosed formula, so you have no way of knowing which transactions you’re actually signing! That’s ridiculous!